Rastafari

Following the 1930 crowning of Ras Tafari (1892–1975) asHaile Selassie (“Power of the Trinity”), Emperor of Ethiopia, several street-corner preachers in Jamaica (among them, Joseph Hibbert, Leonard P. Howell, Robert Hinds, Archibald Dunkley, and Paul Earlington) began asserting that Selassie was a divine personage or the reincarnated Christ. For these Jamaicans, Selassie embodied Marcus Garvey’s vision of black pride, self-reliance, and repatriation to Africa; signaled the restoration of Ethiopia’s ancient glory; and fulfilled theBible’s prophecies of a messianic deliverer. In proclaiming Selassie a messianic figure, they pinned on him their longing for liberation from the legacy of slavery and colonialism.

From the activities of these founding personalities there emerged a set of religious, social, and political beliefs known as Rastafari (or Rastafarianism ), the adherents of which are termed Rastas (or Rastafarians ). From its beginning, Rastafari represented a fundamental critique of the values and institutions of Jamaican society. Rastas’ declaration of adherence to a black messiah indicated their rejection of both European religion and the authority of the colonial state. By referring to Jamaica as Babylon — land of exile, oppression, and exploitation—they expressed their conviction that this was a society with no redeemable values or institutions, and declared their intention to repatriate to their African homeland, from which they had been“stolen.” The Rastas’ explicit promulgation of black superiority—admittedly, an overcompensation for centuries of denigration—signaled not just a rejection of the ideology of white supremacy, but even more a reclamation of blackness and of Africa.

From the 1930s to the 1960s, conflict characterized the relationship between Rastafari and Jamaican civil authorities. The charismatic Rastafarian leader Leonard P. Howell exemplified this conflict in the early decades. For inveighing against the British colonial government, he was repeatedly arrested and imprisoned. Law enforcement also repeatedly raided Pinnacle—the commune he established—and eventually demolished it in 1954. The authorities concluded that Howell was demented and committed him to a metal institution. After his release, Howell lived in relative obscurity until his death in the mid-1980s.

By the late 1940s or early 1950s, the House of Youth Black Faith (HYBF) had emerged as the avant-garde of the Rastafari movement. These young Rastas were even more radical than their elders. They elevated the smoking of ganja (marijuana) to a personal and communal ritual, which they believed aided them in the discovery of their spiritual and cultural identity by breaking through the mental confines imposed by Babylon. They adopted the dreadlocks hairstyle to accentuate their Africanness and to symbolize their rejection of European standards of beauty (favoring fine, straight hair). They are also credited with the development ofdreadtalk, an argot that made their speech often unintelligible to outsiders. Furthermore, HYBF projected an aura of militancy through marches and street meetings, vitriolic language calling down “blood and fire” on Babylon and its agents, and the flaunting of laws against ganja possession and use.

For their marijuana use, dreadlocks hairstyle, and general insubordination, Rastas became subjected to the ire of the agents of social control and public opinion: They suffered frequent arrests on drug charges, scapegoating that saw them blamed for a range of criminal activities, and characterizations in the media as lazy, demented, and disposed to violence. When a few weapons were found in the compound of Claudius Henry, a Rastafarian elder, and when his son was implicated in an alleged plot against the Jamaican government, the repression escalated into indiscriminate harassment, arrests, and forced cutting of the locks of Rastas.

Though a 1960 study of Rastafari by University of the West Indies professors M. G. Smith, Roy Augier, and Rex Nettleford effectively debunked myths about the mental deficiency, laziness, and criminality of Rastas, negative views of Rastafari persisted. These prejudices reached a boiling point in 1963, when an attempt to keep Rastas out of the area surrounding the Rose Hall Great House (a tourist attraction) escalated into a virtual riot in which several people were killed. When the government found “evidence” of the endemic criminality of a West Kingston slum in the mid-1960s, Rastas again took the rap. In an attempt to deal with what it considered entrenched Rastafarian criminality, the government bulldozed the entire shantytown where Rastas and others had constructed shacks on an urban dump.

Though a negative perception of Rastafari persisted among many in Jamaican society after 1960, the Smith, Augier, and Nettleford study helped to influence Jamaica’s political leadership to adopt a less confrontational approach to the Rastafarian phenomenon. In 1961 Norman Manley’s People National Party (PNP) government sent a delegation of civic leaders and Rastas to West Africa and Ethiopia to determine which African countries would be willing to receive Jamaicans desiring to return to the continent of their ancestors. The official report indicated that these countries were only willing to welcome educated and skilled workers. The Rastas of the delegation issued their own report, however, painting a picture of African countries waiting to receive their diasporic children with open arms. Jamaica gained its independence in 1962 under a new Jamaican Labor Party (JLP) government that was less disposed to pursue repatriation for Rastas. Though some Rastas formed their own delegation to make another trip to Africa in 1963, no official repatriation ever took place.

Another measure growing out of the 1960 study was a concerted effort by the Jamaican government to establish cultural and political ties with African countries. This included an invitation to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church to establish itself in Jamaica, and an exchange of visits by Jamaican and African dignitaries. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church eventually established a congregation in Kingston in 1970, and has established further congregations in several other towns since then. Many Rastas identify with or have become members of this church, but they have often come into conflict with its orthodox teachings. The visitor exchange culminated with Haile Selassie’s three-day visit to Jamaica in April 1966. From his arrival until his departure, he was greeted at every public appearance by throngs of Jamaicans, including a multitude of Rastas decked out in their symbolic colors of red, green, and gold. Rastas were among the invited guests at the Vale Royal residence of the prime minister and at fancy hotels where events were held in honor of Selassie. According to reports, some members of the movement were even granted a private audience with the emperor. While Selassie publicly declared that he was not a divine personage, Rastas reported that he confirmed his divinity to them in private, and requested that they work for the liberation of Jamaica before repatriating. After Selassie’s visit, the phrase liberation before repatriation gained currency among Rastas, and the fervor for repatriation seems to have diminished accordingly. Despite the new emphasis on the need for liberation, the visibility and civility of Rastas at public and private functions conferred a measure of legitimacy on the Rastafarian movement.

By the late 1960s, signs of the changing perception and fortunes of Rastafari were becoming evident. One sign was the diffusion of Rastafarian perspectives and symbolism throughout society and particularly among young people and radical intellectuals. Young people, including many from middle-class families, assumed the Rastafarian mode of dress (knitted caps and the colors red, green, and gold), mode of speech, and ideological stance vis-à-vis the oppressive nature of Jamaican society. Many black intellectuals, who had adopted the black nationalism of the Black Power movement in the United States, found a vernacular expression of such nationalism in Rastafari and established dialogue with the movement. This is best exemplified by the Black Power radical Walter Rodney, a history professor at the University of the West Indies, Mona.

Another sign was the growing influence of Rastafari on local popular music. In the 1950s, Rastafari adopted an African drumming style that had been preserved in Jamaica by a cultural group called the Burru. Rastas made this style into their ritual music and regarded it as having mystical power for use in the fight against oppression. In the early 1960s, Count Ossie, a Rastafarian drummer, arranged and accompanied “O Carolina,” which became a hugely popular song in Jamaica. For the first time, Rastafarian rhythms were incorporated into popular music. After the recording of “O Carolina,” Ossie’s compound in East Kingston became a gathering place where local musicians congregated and participated in lengthy jam sessions, thus fostering the exchange of musical ideas.

These and other musicians began to incorporate Rastafarian rhythms into reggae music, and they eventually reproduced the whole range of Rastafarian rhythms on modern instruments.

The incorporation of Rastafarian rhythms into Jamaican popular music was followed by the insertion of Rastafarian spirituality and social criticism into the lyrics of popular songs. Lyricists, whether they were Rastas or not, tended to aim their barbs at the establishment, employing the verbal tools and the critical perspective of Rastafari. No one did this with more clarity and consistency than Bob Marley. His growing social consciousness and his proximity to his Rastafarian neighbors eventually led him to embrace Rastafari. In a short time, Marley made himself the public persona and international ambassador of Rastafari and reggae. Through his considerable repertoire, from “Concrete Jungle” to “Redemption Song,” Marley became the voice of the marginalized, expressing their critical assessment of the values and institutions of the West, their resolve and resilience in the struggle against extreme odds, and their determination to resist and rebel against their oppression.

Despite their activism around issues relating to poverty, the importance of African heritage, repatriation of blacks to Africa, and the legalization of ganja, Rastas have traditionally despised politics, calling it politricks, to indicate their belief that it was marked by deception and trickery. However, some members of the movement have made forays into Jamaica’s electoral politics. Most notable are the candidacies of Ras Sam Brown in 1961, Ras Astor Black of the Jamaica Alliance Movement in 2002 and after, and members of Imperial Ethiopian World Federation Party in 2003. In all instances, Rastafarian candidates received minimal support at the polls. Nevertheless, Rastafarian ideas, symbols, and lingo and Rastafari-inspired songs have been tools of political electioneering in Jamaica, as was particularly evident in the 1970s.

During the lead-up to the 1972 Jamaican general election, the PNP leader, Michael Manley, presented himself as the champion of the poor masses. In doing so, he co-opted many of the ideas and much of the language used by Rastas in their criticism of Jamaica’s sociopolitical establishment. Specifically, he painted the members of the ruling Jamaica Labor Party as agents of Babylon, and presented himself as Joshua (of Biblical fame), presumably appointed by God to “beat down Babylon” and establish justice for all. A central symbol in this political drama was a walking stick continuously brandished by Michael Manley. Manley claimed to have received the stick from Haile Selassie during a visit to Addis Abba. It was dubbed the Rod of Correction and portrayed as symbolic of Manley’s authority, bestowed by Jah (God) or Selassie, to right the wrongs of Jamaican society.

Probably the most effective electioneering tool in Jamaica in the 1970s was reggae music, with its Rastafari-inspired lyrics. Manley and the PNP adopted such songs as “Better Must Come,” “Beat Down Babylon,” and“Dem Ha Fi Get a Beatin” to convey to the masses that they intended to change fundamentally social conditions in Jamaica. Such Rastafarian terms as “One Love,” “Peace and Love,” and “Hail De Man” flowed from the lips of PNP politicians in a streetwise and populist attempt to woo the young and poor who made up the majority of the voting public. While the PNP referenced elements of Rastafari more extensively and managed to win the 1972 and 1976 elections, the JLP was also quick to invoke the vernacular culture deeply influenced by Rastafari. Its campaigners made liberal use of reggae songs, and its leaders, such as Hugh Shearer and Edward Seaga, gave speeches that were laced with Rastafari-inspired street lingo. By the 1980 election, which was won by the JLP, the overt use of Rastafarian references and language was clearly on the wane in political campaigning. Manley had become steeped in Marxist/socialist rhetoric, whereas Seaga, who had become the leader of the JLP, appealed more to the folk-Christian sensibilities of followers of Revivalism and Pentecostalism, religious movements that are even more pervasive in Jamaican society than Rastafari. Seaga had been a promoter of Jamaican folk culture since the 1960s, had done ethnographic research on Revivalism, and had been rumored to be a secret practitioner of its healing arts.

Though politicians may have been self-serving when they co-opted Rastafarian lingo and symbolism as electioneering tools, they unwittingly bestowed legitimacy on both. At the same time, reggae’s status was on the rise. Artists such as Desmond Decker, Toots and the Maytals, and Jimmy Cliff gained international success, while Bob Marley and the Wailers achieved superstardom, making them the epitome of reggae’s cultural ascendancy. Despite earlier misgivings, Jamaicans of all walks of life came to embrace reggae as Jamaica’s cultural gift to the world. Marley was eventually awarded Jamaica’s second-highest honor, the Order of Merit, and at his passing he received a state funeral. Since then, reggae and Rastafari have become a source of inspiration for artistic and cultural production in Jamaica, the Caribbean, and beyond.

From its inauspicious beginnings among the marginalized in Jamaica, Rastafari has blossomed into a global religious and cultural movement. Today Rastafari claims followers throughout the Caribbean, including Cuba; in West and Southern Africa; throughout North America and Europe; in Central and South America, especially Brazil; in New Zealand and Australia; and even in Japan. The spread of Rastafari has been facilitated by international travel and migration and by the worldwide distribution of reggae via the global music industry and communication technology.

The post–World War II era saw the immigration of numerous Jamaicans, including Rastas, to England and North America. When many of the children of these immigrants looked to Jamaica in the 1960s and 1970s for something to counter the alienation they felt in their parents’ adopted homelands, it was Rastafari that provided them with both a critique of alienating Western culture and a sense of self that celebrated their African heritage. Students from other Caribbean islands studying in Jamaica, and Jamaicans traveling to and studying in other parts of the Caribbean, were the main agents of the spread of Rastafarian ideas and practices throughout the Caribbean, especially to Barbados, Cuba, Dominica, and Trinidad and Tobago. Over the years, Rastas have traveled far and wide throughout the world, taking their message with them, and visitors to Jamaica from around the world have also contributed to the dispersal of the Rastafarian message.

Probably even more important than travel and migration has been the spreading of the Rastafarian message through reggae music. Through the global marketing of reggae and the ubiquity of modern communication technology, even people who have never seen a Rasta in the flesh have come in contact with the message of Rastafari and have found resonances with their own experiences and aspirations in the music. Thus, we find reggae and Rastafari inspiring the struggles of people around the world: the Maoris of New Zealand, the Aborigines of Australia, the Punjabis in India, Native Americans, and the Palestinians.

The earliest studies on Rastafari tended to focus on its rejection of Jamaica, its call for repatriation, and its deification of Haile Selassie. Using a label commonly applied to new religious movements in colonial or former colonial societies, these studies identified Rastafari as an example of messianic millennialism (Simpson 1955; Barrett 1977; Kitzinger 1969). The next wave of studies tended to highlight the political dimensions and revolutionary potential of Rastafari and hence saw Rastafari as a call for social change in Jamaica (Nettleford 1970; Owens 1976). The third wave was more serious about taking an ethnographic approach and about exploring the character of the Rastafari movement. These scholars described the contours of the movement, highlighting its cultural, social, and spiritual beliefs and practices (Chevannes 1994; Yawney 1978). Into the twenty-first century, the output is almost too varied for categorization. The spread of Rastafari and its growing globalization have led to mutations and transformations. Most academic studies have built upon the second and third waves mentioned above. In addition, many Rastas have written accounts and interpretations of their experiences; numerous studies of reggae and its relationship to Rastafari have been published; biographies of Rastafarian reggae artists, chiefly Marley, abound; and various studies of Rastafari in a range of locations (Britain, West Africa, South Africa, Brazil, Trinidad, Dominica, Cuba) are now available.

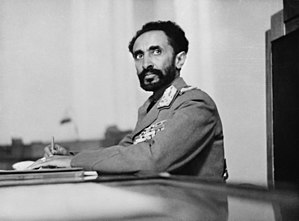

Haile Selassie

On June 30, 1936, a short, seemingly frail man wrapped in a long, black coat addressed the League of Nations in Geneva,Switzerland. He was striking, with chiseled features, light brown skin, a curly black beard, and dark, deep-set, penetrating eyes. His rigid bearing and dignity, almost as much as his impassioned words, captured the attention of the assembled delegates.

Haile Selassie, exiled emperor of Ethiopia, denounced the then-recent invasion and conquest of his country by Italy, a precursor of the continued aggression that would lead to World War II. He demanded the League take concerted action against the Italians, warning, “It is a question of collective security; of the very existence of the League; of the trust placed by states in international treaties.… It is international morality that is at stake.” He prophetically stated, “It is us today. It will be you tomorrow.”

Despite the failure of the League to act upon his appeal, Haile Selassie’s dramatic speech turned him into an international figure overnight. No longer was he just the obscure ruler of a little-known northeast African kingdom. Instead, he became recognized as a world leader and an acknowledged symbol of resistance to fascism—the dictatorial system of government that grew in various European nations during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s.

With British help, Ethiopia was liberated from the Italians in 1941 and Haile Selassie returned to rule for more than 30 years with the absolute power of a medieval king—holding court, dispensing gifts from a golden cashbox, and throwing coins to peasants on trips throughout his empire. Abroad, he was worshipped as a divine figure; in Jamaica, he is still considered by Rastafarians to be the spiritual leader of blacks worldwide.

As many African nations gained independence from European domination in the turbulent 1950s and 1960s, Haile Selassie stood out as an international statesman. His leadership in the subsequent Pan-African movement was rewarded when the Organization of African Unity (OAU) established its headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital. But growing social unrest, the continued poverty-stricken existence of most Ethiopians, and then a widespread famine led to his overthrow in 1974; he died the following year.

At a Glance…

Born Tafari Makonnen, July 23, 1892, in Ejarsa Goro, Harer province, Abyssinian Empire (later Ethiopia); died August 27, 1975, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; son of Ras Makonnen (governor of Harer province and chief adviser to Emperor Menelik II) and Yishimabet Ali; married Wayzaro Menen (name some times spelled Waizero Menin; great-granddaughter of Menelik II) in 1911; children: seven (six with his wife, one before his marriage). Education: Private European tutors. Religion: Coptic Christianity.

Commander of local militia, 1905; provincial governor of two progressively larger provinces, 1906-10, culminating in governorship of Harer province, 1910-16; aided overthrow of Ethiopia’s emperor, 1916, becoming prince, regent, and heir to the throne; negotiated Ethiopia’s membership in the league of Nations, 1923; toured European nations, 1924; named king, 1928; crowned emperor, 1930; defeated by invading Italian army, went into exile, then addressed League of Nations, 1936; returned to power, 1941; helped establish Organization of African Unity (OAU), 1963; overthrown by coup, 1974. Author of autobiography My life and Ethiopia’s Progress, l892-1937.

Haile Selassie was born in a round mud-and-wood hut near the ancient walled city of Harer in 1892, when Ethiopia was still known as the Abyssinian Empire. Named Tafari Makonnen, he was the tenth child born to Ras Makonnen, a prince (or ras) and. governor of the Harer province, and his wife, Yishimabet Ali; he was the only one of their eleven children to survive through adulthood.

Abyssinia was little changed through the centuries: a poor, proud, fiercely independent African empire with several religious groups—Christians, Muslims, Jews, and ani-mists—ruled by a constantly warring network of kings, princes, dukes, and lords. Tafari was an Amhara, the dominant ethnic group that had adopted Coptic Christianity in the year 325 AD. Coptics hold that Christ was solely divine, a belief later denounced as heretical by most of the Christian world except in Egypt and Ethiopia.

His father, Makonnen, was a cousin, confidant, and chief adviser to Emperor Menelik II, a shrewd and powerful ruler. After Italy invaded Abyssinia in 1895, Menelik’s army soundly defeated their forces at the battle of Adowa the following year, preventing the country from being colonized. Over the next few years, Menelik enlarged his empire, establishing Addis Ababa in the center of the kingdom as his capital. He began to centralize power and modernize the country, ending centuries of constant warfare.

When Tafari was 18 months old, his mother died giving birth to one of his siblings. Young Tafari grew up with a sound education in Abyssinian and Coptic traditions, and he was tutored in European thought and ideas by Father Andre Jarosseau, a French missionary priest. Such exposure to foreign ways and thinking was extremely rare for an African son. Tafari proved to be a model student— intelligent, hardworking, with an excellent memory and attention to the smallest detail—capacities that would serve him well throughout his life.

Recognizing his abilities, his father proclaimed him de-jazmatch (commander) of a local militia in 1905 at the age of 13, and established a separate household for him with his own servants and soldiers. Makonnen died the following year, entrusting Tafari to the care of Menelik II. The emperor summoned young Tafari to court and appointed him governor of a small province.

Reform and Intrigue

Tafari was a progressive administrator whose policies increased the power of the central government at the expense of the feudal nobility. He developed a salaried civil service, lowered taxes, and created a court system that extended legal rights to the peasantry. Promoted to a larger province in 1908, two years later he was made governor of Harer, just like his father. And in 1911, he married Wayzaro Menen, a great-granddaughter of Menelik. During the course of their marriage, they had six children, and they remained together until her death in 1961.

Menelik died in 1913 and his grandson, Lij Yasu, became emperor. But Yasu was seen as pro-Muslim, alienating Ethiopia’s Christian majority. Tafari became the rallying symbol for opposition noblemen and high church officials, who cunningly maneuvered Yasu’s overthrow in 1916. Zauditu, Menelik’s daughter, became empress, the first female to rule the nation of Ethiopia since the Queen of Sheba, while Tafari was named a prince (ras) as. well as regent and heir to the throne. Ras Tafari was interested in modernizing Ethiopia; Zauditu was conservative and more concerned with religion than politics. The two maintained an uneasy alliance as various rival factions of nobles vied for power.

The young prince proved to be the master of intrigue and survival. Gradually, he replaced conservative members of the Council of Ministers with his own pro-reform supporters. By 1919 he felt secure enough to begin his program of modernization by creating a centralized bureaucracy. Two years later, he established the first regular courts of law in the country. Ethiopia’s first printing press began operating in 1922, soon followed by the introduction of a regularly published newspaper, as well as motorcars, electric generators, telephone service, and a reformed prison and justice system.

International Recognition

Greater success awaited. Ras Tafari turned his attention to foreign affairs, gaining Ethiopia’s admission to the League of Nations in 1923. The following year, he visited France, Italy, Sweden, Greece, and England, garnering favorable recognition from the international press.

His trip coincided with the growing interest among North American blacks in rediscovering their cultural heritage. Seeing a noble, dignified African leader of an independent nation dealing as an equal with European rulers made an indelible impression. Jamaicans, in particular, were in awe, identifying him as the future king of blacks everywhere in the world. These idolizers, called Rastafarians, started a new religion in his honor that continues today.

Back home, Ras Tafari profited financially from his modernization program and international contacts by enacting a tax on all imports. He used his new fortune wisely, financing the foreign education of a new generation of future Ethiopian government ministers and buying the loyalty of the army. In 1928 his growing supporters demanded that Zauditu name him king. With only limited followers of her own, the empress agreed, appointing Tafari negus (king). Two years later, rebels allied with her attacked the capital but were defeated by Ethiopia’s armed forces. Two days after the battle, Zauditu died—some claimed from poison. Tafari was coronated as emperor, taking the name Haile Selassie ( “Power of the Trinity”), in a ceremony widely covered by the international press.

The new emperor enacted Ethiopia’s first constitution in 1931. It proclaimed all Ethiopians equal and united under one law and one emperor; it also created a two-chamber parliament with a popularly elected lower house, though the emperor retained the right to overthrow any parliamentary decision. Traditional church law was supplanted by the country’s first legal code, and all children born to slaves were eventually freed.

His continued efforts toward modernization and centralizing power were cut short in 1935. Mussolini, the Italian fascist leader, was eager to avenge his country’s 1895 defeat by Menelik and enhance his belligerent image. He dispatched a 250,000-man modern army equipped with superior weaponry, airplanes, and poison gas to invade and conquer Ethiopia. It was the first exhibition of the fascist aggression that would eventually lead to World War II. Defeated, Emperor Haile Selassie fled his country in 1936, appealing without success to the League of Nations for assistance before going into exile in England. Ethiopia had lost its independence for the first time in recorded history.

Once World War II began, a joint force of British soldiers and Ethiopian exiles recaptured Addis Ababa, restoring Haile Selassie to power in 1941. During the next decade he improved health care, enhanced transportation, increased foreign trade, expanded education, and created the country’s first college. But he made no attempt to reform the feudal agricultural system that maintained class distinctions and limited land ownership. Throughout the 1950s he extended his power in Ethiopia’s outlying provinces and maneuvered to annex its neighbor, the former Italian colony of Eritrea, to provide landlocked Ethiopia with a port on the Red Sea. Success finally came in 1962 when Eritrea became an Ethiopian province.

Haile Selassie celebrated his 25th year as emperor in 1955, using the occasion to present a revised constitution. Though it gave the appearance of liberalizing the political system and broadening the power of parliament, in reality all power still resided in the emperor and his one-party government. As proof, the country’s first general election in 1957 resulted in a parliament composed almost entirely of members of the landlord class. But the outward show of reform stimulated the desire of many for a taste of the real thing. When the emperor was visiting Brazil in 1960, dissidents backed by the Imperial Guard and students at the university seized control of Addis Ababa. They demanded a constitutional monarchy with genuine democracy, fundamental economic and agricultural reform, and a concerted effort to end the chronic poverty of most Ethiopians.

The coup failed and many of its leaders were publicly executed. But their demands pinpointed the growing dissatisfaction with Haile Selassie’s rule at home. The attempted overthrow also jolted his sense of security. From this point on, he began to side with Ethiopia’s conservative faction rather than its modernizers. No longer would he be a force for change within his own country.

Instead the emperor turned his attention to foreign affairs, partly to enhance his international status and partly to take his compatriots’ minds off the lack of domestic reforms. Instead of focusing on Europe as in the past, he concentrated on Africa, becoming a role model and elder statesman to many leaders of the newly independent African nations.

Haile Selassie became a leader in the Pan-African movement, stressing African unity to deal with common problems and concerns. He supported independence for former European colonies, condemned South Africa’s foreign and internal policy of racial segregation (apartheid), and sought to limit French nuclear tests in the Sahara. He also took a leading role in the formation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU). Having the organization establish its permanent headquarters in Addis Ababa further enhanced his international prestige.

More and more of Haile Selassie ’s time was spent traveling in foreign countries and away from Ethiopia. He successfully mediated the border dispute between Morocco and Algeria in 1963 and then intervened on the side of Nigeria during its bloody civil war, which began in the late 1960s when Christians in the South broke away and formed a separate nation called Biafra. (Biafra later surrendered to federal troops.)

Unrest at Home

While he was being honored abroad, trouble was brewing at home. Islamic Eritrean rebels had begun a civil war in 1962, seeking their independence from Christian Ethiopia. The struggle would last into the 1980s. Neighboring Somalia demanded the return of the Ogaden region. That conflict, too, would escalate to warfare in 1977. The United States and Israel, fearful of an Islamic Eritrea and Somalia, supported Ethiopia with advisers and military aid. Meanwhile, demands by dissidents and students continued to escalate. The educated elite’s mounting frustration with the lack of jobs and democratic reforms in Ethiopia was fueled by economic stagnation, rising unemployment, and growing urban poverty. In December of 1969 a student protest turned violent; guards opened fire, killing 23 and wounding 157.

In 1973 a drought and crop failure caused a widespread famine. Tens of thousands of Ethiopians starved while the emperor reportedly denied the existence of any problem. Angry students aided foreign journalists to surreptitiously observe and then report on the desperate conditions. Western governments began to distance themselves from the fading emperor. At the same time, the Arab oil embargo quadrupled the price of oil, depleting the Ethiopian treasury and sending prices skyrocketing. The government responded with austerity measures; the frustrated populace countered with major demonstrations.

The next year, many of the army’s junior officers mutinied, forcing the emperor’s cabinet to resign. The successful mutineers formed a dergue (military junta or council) and began vying for total control of the government, accusing the emperor of embezzling millions and causing the famine. Finally, in September of 1974, 82-year-old Haile Selassie was arrested and taken away to prison. More than a half century of actual rule by the emperor had come to an end. He was never seen in public again and was reported to have died and been buried without ceremony the following year.

During the violent years after his overthrow, Ethiopia nearly disintegrated. Infighting among members of thedergue became deadly. Hundreds of former political leaders were executed. Major (later Colonel) Mengistu Haile Mariam took over and turned the country into a Marxist state. Thousands of internal political opponents were massacred. The wars with Eritrea and Somalia drained the budget and devastated the countryside. Combined with another drought and crop failure in 1983, millions of Ethiopians either starved or fled to refugee camps in the Sudan and Somalia.

Some of Mengistu’s internal opponents allied with Eritrean guerrillas in 1989 to topple his rule two years later. A semblance of peace descended on Ethiopia, though the ethnic and tribal conflicts unleashed during the 17-year military dictatorship still threatened to undo the kingdom that Haile Selassie had spent a lifetime creating.

The Legacy

When Haile Selassie took power as regent in 1916, Ethiopia had progressed little through the centuries. Though independent, it was dominated by feudal lords wielding nearly absolute power, ruling through archaic laws and traditions. He set about modernizing the country, abolishing ancient practices, promoting reform, and creating a powerful centralized government. Ethiopia was opened to the outside world and its emperor became recognized in international circles.

But Haile Selassie always ruled absolutely. As times changed and his citizens demanded more political freedom and democracy, he grew more conservative. At the same time, poverty and illiteracy were taking their toll on the Ethiopian people. Having lost touch with political reality, the emperor refused to surrender his power and was overthrown. However, despite his downfall, he continues to be remembered as “Lion of Judah, King of Kings, Elect of God”—and as a charismatic, near-mythic figure in Ethiopian politics for more than half a century.

Marcus Garvey

In 1920, Marcus Garvey , a Jamaican born and founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), worldwide attention with his "back to Africa" movement for blacks. Garvey encouraged black people to be proud of who they are and to become independent of white supremacy. The origin of the black consciousness movement and civil disobedience movement in the U.S. were direct consequences of Garvey's work. During a speech, Garvey declared: "Look to Africa where a black king will be crowned, he will be the savior." Some years later, on 2 November 1930 , was Ras Tafari Makonnen was crowned king of Ethiopia. He gave himself the title of "Emperor Haile Selassie (Power of Trinity) I, conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Elect of God and King of Kings of Ethiopia". Selassie's coronation was immediately seen as the fulfillment of Garvey's prediction about the black king can in a sense, as the official start of the Rastafarian faith. Rastafarians his title slightly modified and referred to him as "His Majesty, Emperor Haile Selassie I, King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Elect of God, Light of the World, King of Zion." Garvey, who in addition to Selassie still today the most important figure in the Rastafarian faith seen, was never himself a Rastafarian. He Selassie even in publicly criticized slavery allegedly still operating in Ethiopia and him not as the "savior" considered. Garvey continued his uplifting black people until his death in London (1940), after which his body was returned to his native Jamaica .

Classical period

In the period between 1930 and early 1960 's, known as the "classic period", Rastafarianism was a Jamaican religious movement with little influence or outward. As today is still the case, many Rastafarians outside the cities in camps in the Natural lived under the authority of an elder or "oldest". Some camps are similar to monasteries, with men and women who live apart. Others are in appearance and organization again similar to statjies in West Africa . Life in the statjies is simple, with ital food that the women are prepared, and the ritual smoking of ganja to the real spiritual consciousness to achieve. Initially, the Rasta locks only by those who wore the Nazarite vow (Numbers 6: 2-8) wrote, but it later became popular among other Rastas also. "Another very interesting development in this period occurred in Jamaica. The Ethiopian World Foundation (EWF), which used by Selassie's government and established close ties with the Ethiopian Orthodox Church had a branch on the island began. This branch of the EWF was soon by Rastafarians "hijacked" and the subsequent interaction between the two groups, the orthodox Rastafarianism officially established. Meanwhile, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church of Ethiopia began on Jamaica, and although not all Rastafarians accept the orthodox views had not yet all in varying degrees are affected.

Exodus to Ethiopia

The one thing all Rastafarians agreed, was that Haile Selassie "divine" and that he was the black people of the world would help to return to Africa (Ethiopia). Although some a mystical interpretation of the return to Africa declared after Selassie's death, the Rastas in the beginning everyone expects to himself physically to emigrate to Africa. This expectation gave Rastafarianism a political dimension similar to Zionism given. While political revolutionary in the rest of the world screamed "power to the people" have "let my people go" the Rastas's slogan became. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, some Rastafarians in frustration because the trip to Africa does not occur, the Rastafarian principles of non-violence and abandoned in various shooting battles with British troops in Jamaica clashed. This world is a very negative image of Rastafarianism concerned that later, with the popularity of reggae music, weather would change. By the 1960s, Rastafarianism grew and the ideal to return to Africa in theory have probably looked for Rastas. While the outside world to have limited knowledge taken from the faith and its objectives, it was still mainly to Jamaica and the Caribbean is limited. Rastafarianism would be the end of the decade known worldwide with the advent of new "prophet" - Bob Marley .

Grounation day

The growth of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in Jamaica led to Haile Selassie on 21 April 1966 on the island arrived on an official visit. This day since by Rastafarians as a special holiday, Grounation Day, celebrated. There are different versions of Selassie's impression of the Rastafarians during his visit. He does have occasional discussions held with a group of Rastafarian elders, but again there are different versions about during this historic meeting were discussed.Most versions agree well with that Selassie (perhaps precisely for fear of a mass emigration to Ethiopia) to the elders would suggest to Jamaica first "build". This has Selassie, or Jah for his followers, to a large extent many Rastas' enthusiasm dampened as soon as possible to emigrate to Ethiopia.

Rastafarianism today

Rastafarian groups

Most Rastafarians are today very concerned about the finer details of the teachings of their faith. They believe in the basic tenets of Rastafarianism, but not necessarily belong to a particular organized group or order. There is today a few organized Rastafarian groups which can be noted. The "Twelve Tribes of Israel" (not related to the Black Hebrew group with the same name) is probably the biggest. This group believes that Haile Selassie is actually Jesus Christ who returned to Earth . The return therefore already occurred. Followers of "Prince" Edward Emmanuel, who claimed that he was one of the divine Trinity along with Haile Selassie and Marcus Garvey, is probably the best georganiseerdes. The group's teachings, priestly hierarchy and liturgy are clearly defined and they perform a kind kloosterbestaan with strong orthodox characteristics. The Zionist Coptic Church (Zion Coptic Church), a boom in the 1960s experienced when white hippies they turned Rastafarianism. This group regards itself as a legitimate orthodox church that certain aspects of traditional Rastafarian culture adopted. Some of the group's thinking on the border Gnosticism .Members of the Zionist Coptic Church is often criticized because some of them, although they still wear Rasta dreadlocks and ganja smoke, also financially very wealthy and allegedly the largest landowners in Jamaica is.

No comments:

Post a Comment